Stadium safety: Those who are about to cheer salute you

Posted on Sep 5, 2022 by Xtreme Staff

Keeping track of stadium safety is one of sports’ greatest priorities. Luckily, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel – or the Colosseum

//Words by Neal Romanek//

Intelligent crowd management is one of the most important skill sets in sports. Decades of trial and – often tragic – error have led to a status quo where venues are, more often than not, a place you would feel comfortable bringing your kids.

Controlling fans is as old as competition itself. The ancient Olympic Games entirely forbade the attendance of women, on pain of death. The story is that only Greek men were considered citizens, and since the Olympics was an important political event, it wasn’t appropriate for females to attend. Of course, the real reason was that husbands did not want their wives watching completely naked young men, with oiled-up bodies, being far more awesome than they were.

In one famous incident, a widow named Callipateira – whose son was competing in the Games – had sneaked into the venue disguised as a trainer. After he won, she jumped onto the field to celebrate – blowing her cover. Organisers let her go without a fine, out of respect for her son’s achievements, but a regulation was passed thereafter requiring all trainers to strip before entering the arena.

Keeping track of stadium safety is one of sports’ greatest priorities. Luckily, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel – or the Colosseum

//Words by Neal Romanek//

Intelligent crowd management is one of the most important skill sets in sports. Decades of trial and – often tragic – error have led to a status quo where venues are, more often than not, a place you would feel comfortable bringing your kids.

Controlling fans is as old as competition itself. The ancient Olympic Games entirely forbade the attendance of women, on pain of death. The story is that only Greek men were considered citizens, and since the Olympics was an important political event, it wasn’t appropriate for females to attend. Of course, the real reason was that husbands did not want their wives watching completely naked young men, with oiled-up bodies, being far more awesome than they were.

In one famous incident, a widow named Callipateira – whose son was competing in the Games – had sneaked into the venue disguised as a trainer. After he won, she jumped onto the field to celebrate – blowing her cover. Organisers let her go without a fine, out of respect for her son’s achievements, but a regulation was passed thereafter requiring all trainers to strip before entering the arena.

Romans turned sports from religio-political ritual into big business with their magic formula of ‘bread and circuses’, so the building of venues became high art. But although the Romans were geniuses at tech, they still couldn’t imagine a fully egalitarian society (building an empire on the back of slave labour will do that). Emperor Augustus, first and best among control freaks, established the Lex Iulia Theatralis, with rigid specifications about where each social group was to sit in public amphitheatres. This included – sure enough – women separate from men, up in the nosebleed seats.

Romans turned sports from religio-political ritual into big business with their magic formula of ‘bread and circuses’, so the building of venues became high art. But although the Romans were geniuses at tech, they still couldn’t imagine a fully egalitarian society (building an empire on the back of slave labour will do that). Emperor Augustus, first and best among control freaks, established the Lex Iulia Theatralis, with rigid specifications about where each social group was to sit in public amphitheatres. This included – sure enough – women separate from men, up in the nosebleed seats.

Imagine the grains of sand in an egg timer: the quickest flow is down the middle. But if you look at a crowd, it often moves fastest around the edges

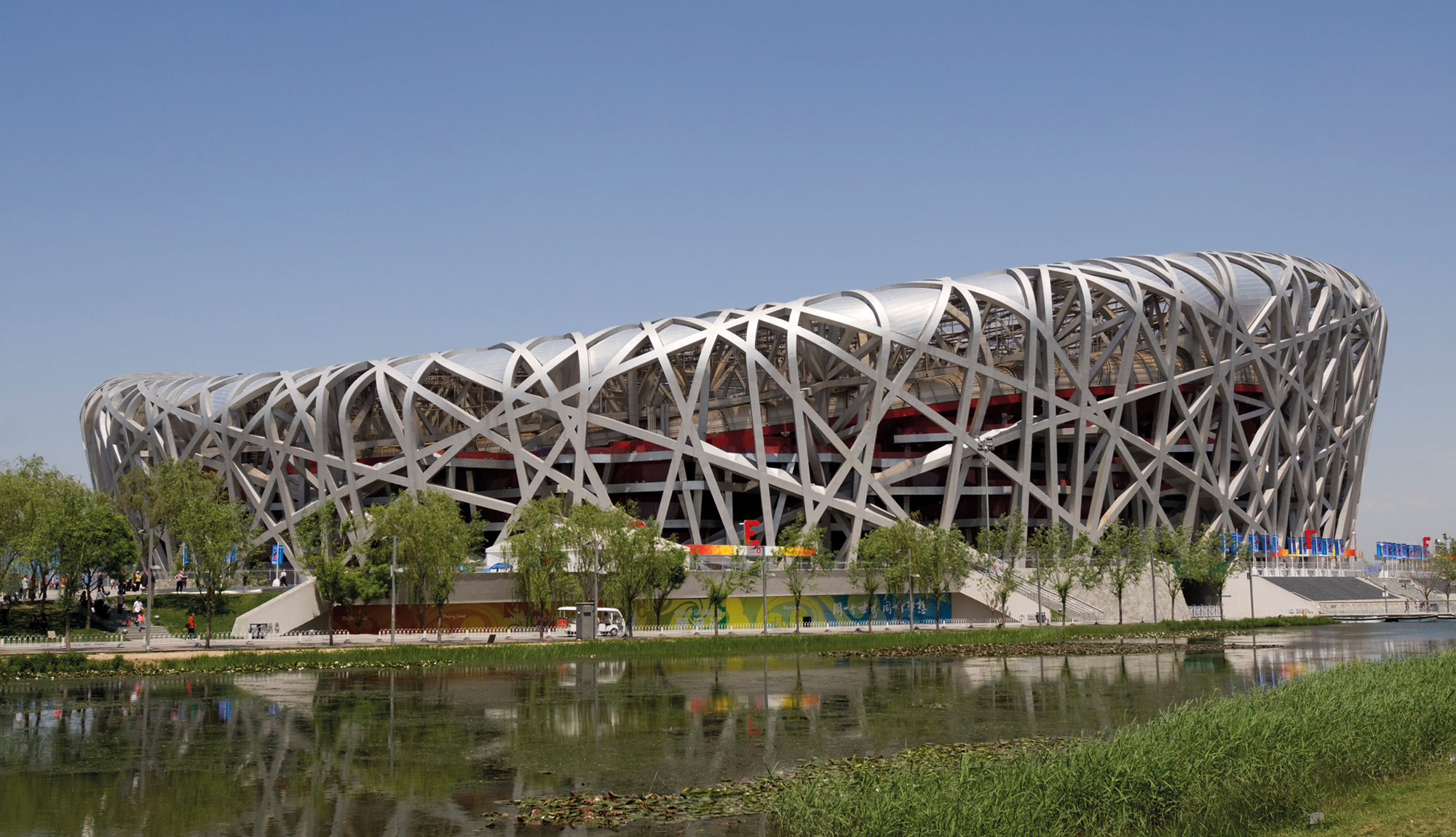

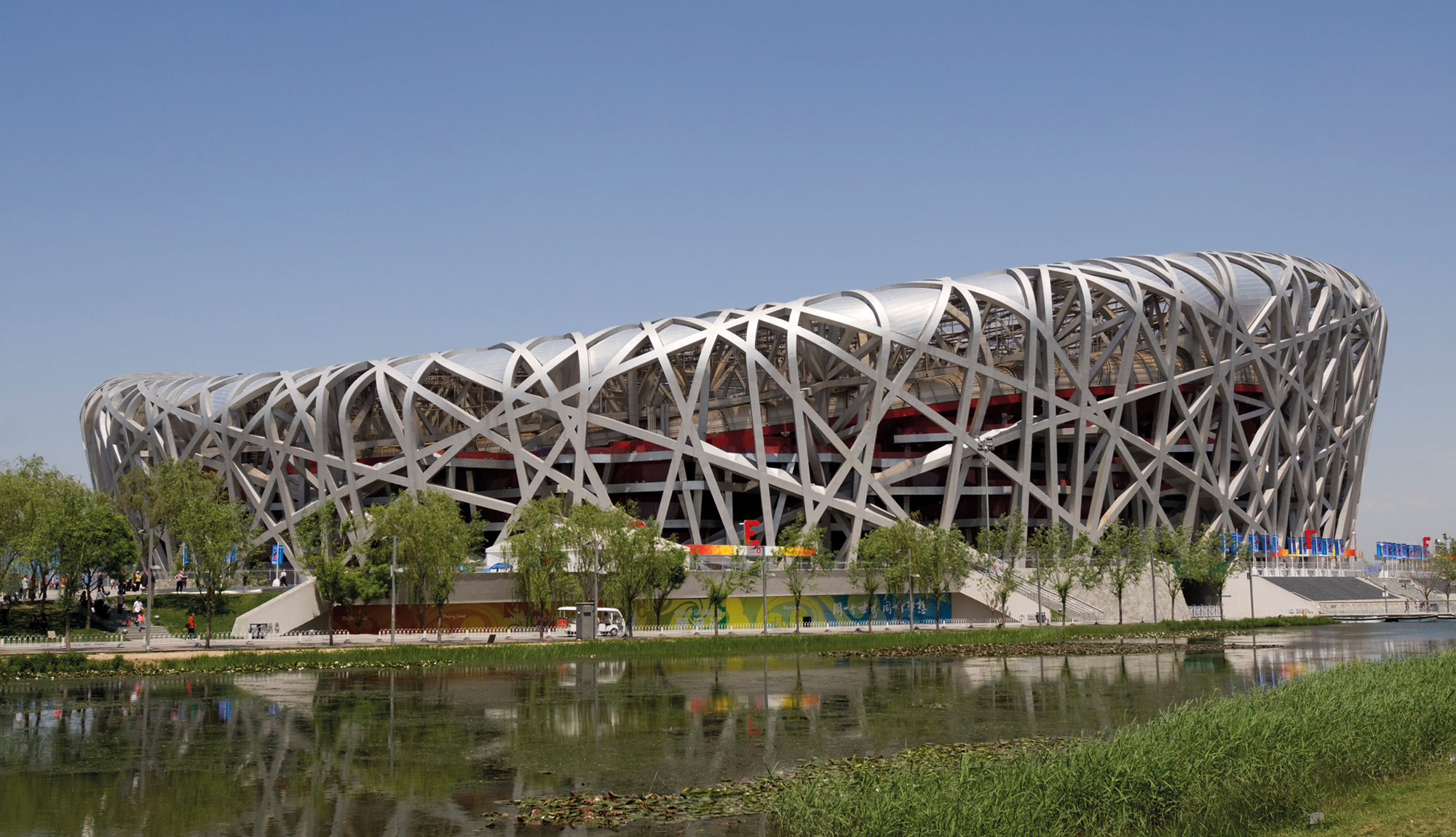

The Colosseum in Rome was built in the 1st century CE by the emperor Vespasian and could host an average audience of 65,000 people – even 80,000 at a pinch (Beijing’s Bird’s Nest Stadium, home of the 2008 Olympics, has a capacity of 80,000). It was the largest amphitheatre ever built – and as an ‘amphitheatre’ per se, it still is – but other venues around the Empire could still comfortably hold many thousands of people. The stadium at Capua, where Spartacus fought, had a capacity of 60,000, and Pompeii’s held 30,000. In fact, a lot of problems encountered by stadium operators today were faced – and solved – in the sports venues of ancient Rome.

Classical geometries

The Romans understood how to move crowds around – Rome’s crazily efficient deployment of armies, for example, was the terror of the ancient world. Ancient ruins that history has bequeathed us tend to highlight the architecture, materials and craftsmanship that went into them, but the Romans were always thinking of buildings as technologies for moving and housing humans.

“If you look at the geometric layout and design of the Roman stadium in Pompeii – an example of one within a city complex – as well as the optimisation and movement of people, they had it pretty close to mathematically perfect,” says Professor Dr G. Keith Still, a world renowned expert on crowd safety, planning and education.

Professor Still has advised some of the world’s biggest event producers on how to make crowded spaces safer and more efficient. Among his clients are major sports venues, building developments and public events, supporting the Saudi government on Hajj projects. His study of the geometries of classical architecture reveal a key to effective crowd management – making sure fans have a good time is as much about physics and mathematics, as crowd psychology.

The Colosseum in Rome was built in the 1st century CE by the emperor Vespasian and could host an average audience of 65,000 people – even 80,000 at a pinch (Beijing’s Bird’s Nest Stadium, home of the 2008 Olympics, has a capacity of 80,000). It was the largest amphitheatre ever built – and as an ‘amphitheatre’ per se, it still is – but other venues around the Empire could still comfortably hold many thousands of people. The stadium at Capua, where Spartacus fought, had a capacity of 60,000, and Pompeii’s held 30,000. In fact, a lot of problems encountered by stadium operators today were faced – and solved – in the sports venues of ancient Rome.

Classical geometries

The Romans understood how to move crowds around – Rome’s crazily efficient deployment of armies, for example, was the terror of the ancient world. Ancient ruins that history has bequeathed us tend to highlight the architecture, materials and craftsmanship that went into them, but the Romans were always thinking of buildings as technologies for moving and housing humans.

“If you look at the geometric layout and design of the Roman stadium in Pompeii – an example of one within a city complex – as well as the optimisation and movement of people, they had it pretty close to mathematically perfect,” says Professor Dr G. Keith Still, a world renowned expert on crowd safety, planning and education.

Professor Still has advised some of the world’s biggest event producers on how to make crowded spaces safer and more efficient. Among his clients are major sports venues, building developments and public events, supporting the Saudi government on Hajj projects. His study of the geometries of classical architecture reveal a key to effective crowd management – making sure fans have a good time is as much about physics and mathematics, as crowd psychology.

Still’s education was in physical sciences, before pursuing an early career in operations management and electronics design.

“I had the right mindset when, one day, I found myself stuck in a queue at the turnstiles and realised, ‘Wait a minute, this isn’t physics!’” Still recalls. “Imagine the grains of sand in an egg timer: the quickest flow is down the middle. But if you look at a crowd, it turns out it often moves fastest around the edges. As I was stuck in a queue watching this, I thought, ‘Maybe we’ve got the maths for crowd movement wrong?’ And that led to a PhD in crowd dynamics.” Still’s research observed that the success of ancient stadium architecture depended on obeying mathematic principles. These were informed by an understanding that the entities moving through spaces were intelligent, responding to their environment and each other.

The ancient Romans learned through their mistakes. One of the worst disasters in sports history occurred in 27 CE, when a wooden gladiatorial amphitheatre collapsed onto spectators and shops in the arcade, killing about 20,000 people.

“The Colosseum in Rome, Pompeii stadium and the earlier Greek stadium at Ephesus put a lot of thought into the geometry of moving people around complex spaces. Pompeii had its toilets built outside the arena,” Still explains. “There was a National Geographic programme looking into crowd evacuation at the Colosseum compared to the Bird’s Nest Stadium in Beijing – and the Colosseum stood up as being damn near perfect.”

Clear line of site to the vomitorium

A critical factor in any sports space is the human being. The fact that people are pretty much the same now as they were 10,000 years ago means some principles are going to hold, no matter what.

“Various elements of a stadium are fixed because of the human frame. Take sight lines – there’s an optimal rake for placing people. At a concert on flat ground, you can’t see past anyone sitting in front of you, but at a cinema everyone gets perfect line of sight. The rake, angles of view and available space are all mathematical relationships. An audience’s level of enjoyment is a consequence of getting the geometry right.”

Still’s education was in physical sciences, before pursuing an early career in operations management and electronics design.

“I had the right mindset when, one day, I found myself stuck in a queue at the turnstiles and realised, ‘Wait a minute, this isn’t physics!’” Still recalls. “Imagine the grains of sand in an egg timer: the quickest flow is down the middle. But if you look at a crowd, it turns out it often moves fastest around the edges. As I was stuck in a queue watching this, I thought, ‘Maybe we’ve got the maths for crowd movement wrong?’ And that led to a PhD in crowd dynamics.” Still’s research observed that the success of ancient stadium architecture depended on obeying mathematic principles. These were informed by an understanding that the entities moving through spaces were intelligent, responding to their environment and each other.

The ancient Romans learned through their mistakes. One of the worst disasters in sports history occurred in 27 CE, when a wooden gladiatorial amphitheatre collapsed onto spectators and shops in the arcade, killing about 20,000 people.

“The Colosseum in Rome, Pompeii stadium and the earlier Greek stadium at Ephesus put a lot of thought into the geometry of moving people around complex spaces. Pompeii had its toilets built outside the arena,” Still explains. “There was a National Geographic programme looking into crowd evacuation at the Colosseum compared to the Bird’s Nest Stadium in Beijing – and the Colosseum stood up as being damn near perfect.”

Clear line of site to the vomitorium

A critical factor in any sports space is the human being. The fact that people are pretty much the same now as they were 10,000 years ago means some principles are going to hold, no matter what.

“Various elements of a stadium are fixed because of the human frame. Take sight lines – there’s an optimal rake for placing people. At a concert on flat ground, you can’t see past anyone sitting in front of you, but at a cinema everyone gets perfect line of sight. The rake, angles of view and available space are all mathematical relationships. An audience’s level of enjoyment is a consequence of getting the geometry right.”

One of the failures at the Stade de France was that Bluetooth connection on fans’ phones had to be turned on to get tickets verified

Still notes that the Colosseum’s lines of sight, number of egress points and people feeding each vomitorium were all based on

principles of Greek mathematics and geometric analysis. (Fun fact: a vomitorium is an entrance or exit passage out of the amphitheatre, not a place to intentionally eject that day’s lunch.)

“Apply that to buildings and you have an intuitive sense of how to move from one place to another. Get the geometry right and it becomes far more instinctive to follow your nose. We have found in our stadium work that people will often try a configuration, get it wrong a few times, then eventually iterate into something that’s nearly correct. Well, you can get it right in the first instance if you understand the maths.”

In Still’s view, good venue design – like quality food, stories or clothing – is always built around human experience.

“If you find yourself getting disorientated in a built space, that’s because the architects got it wrong. But if you don’t need to think at all about how to get from A to B, that’s because they got it right.”

Still notes that the Colosseum’s lines of sight, number of egress points and people feeding each vomitorium were all based on

principles of Greek mathematics and geometric analysis. (Fun fact: a vomitorium is an entrance or exit passage out of the amphitheatre, not a place to intentionally eject that day’s lunch.)

“Apply that to buildings and you have an intuitive sense of how to move from one place to another. Get the geometry right and it becomes far more instinctive to follow your nose. We have found in our stadium work that people will often try a configuration, get it wrong a few times, then eventually iterate into something that’s nearly correct. Well, you can get it right in the first instance if you understand the maths.”

In Still’s view, good venue design – like quality food, stories or clothing – is always built around human experience.

“If you find yourself getting disorientated in a built space, that’s because the architects got it wrong. But if you don’t need to think at all about how to get from A to B, that’s because they got it right.”

The human problem

After earning his PhD, Still started to investigate the causes of crowd related accidents, and also became involved in the associated litigation. Identifying where trouble spots are, before there’s a problem, is essential.

In his workshops, he questions students about how often they’ve been at a venue and felt their safety was threatened. Most of the hands go up. However, those regular near misses usually go unreported. It’s only incidents like recent unrest and police action at the Champions League final in the Stade de France – or crowd trouble at Wembley during the Euro 2020 final – that trigger investigation and analysis. The ingredient that can make sports spaces unpredictable is human emotion. Stadiums are places of elation, grief, rage, disappointment – all happening within a few metres of each other. Team rivalries can lead to tipping points that turn anonymous crowds into dangerous entities.

Innovations for monitoring and analysis help teams respond to bottlenecks in real time, or provide deep analysis of how fans behave in various scenarios. In addition to human eyes on video monitors, some tech uses low-energy radio absorption to detect crowd density live, while others work with AI to evaluate live video. But technology won’t help if the basic principles of venue design aren’t right. Even with effective monitoring in place, by the time teams realise there is a problem, it may be too late to do anything about it.

“One of the failures at the Stade de France incident this year was that Bluetooth connection on fans’ phones had to be turned on to get their tickets verified. And we’ve seen other stadiums with electronic ticket checking run into problems when the Wi-Fi has gone down,” insists Still.

Technology can speed things up, but moving people more quickly sometimes creates as many problems as it solves. If e-tickets allow the venue to fill up rapidly, concourses need to be equipped to handle that higher density of traffic, which will affect pressure on concessions and other vendors.

The human problem

After earning his PhD, Still started to investigate the causes of crowd related accidents, and also became involved in the associated litigation. Identifying where trouble spots are, before there’s a problem, is essential.

In his workshops, he questions students about how often they’ve been at a venue and felt their safety was threatened. Most of the hands go up. However, those regular near misses usually go unreported. It’s only incidents like recent unrest and police action at the Champions League final in the Stade de France – or crowd trouble at Wembley during the Euro 2020 final – that trigger investigation and analysis. The ingredient that can make sports spaces unpredictable is human emotion. Stadiums are places of elation, grief, rage, disappointment – all happening within a few metres of each other. Team rivalries can lead to tipping points that turn anonymous crowds into dangerous entities.

Innovations for monitoring and analysis help teams respond to bottlenecks in real time, or provide deep analysis of how fans behave in various scenarios. In addition to human eyes on video monitors, some tech uses low-energy radio absorption to detect crowd density live, while others work with AI to evaluate live video. But technology won’t help if the basic principles of venue design aren’t right. Even with effective monitoring in place, by the time teams realise there is a problem, it may be too late to do anything about it.

“One of the failures at the Stade de France incident this year was that Bluetooth connection on fans’ phones had to be turned on to get their tickets verified. And we’ve seen other stadiums with electronic ticket checking run into problems when the Wi-Fi has gone down,” insists Still.

Technology can speed things up, but moving people more quickly sometimes creates as many problems as it solves. If e-tickets allow the venue to fill up rapidly, concourses need to be equipped to handle that higher density of traffic, which will affect pressure on concessions and other vendors.

Stadiums that are decades old won’t have been designed with this rate of traffic flow in mind. Mass notifications may have a powerful impact on managing crowds, or directing people to better access of services, but these have to be considered in their emotional context. Notifying fans that there’s no wait at the bar almost guarantees a stampede.

“Information systems associated with transit are good and effective,” maintains Still, “providing you understand the consequences of your words. Rather than saying: ‘There are five spaces left in this area’, when you have 1000 people that want to get in, it’s better to say: ‘Avoid the following areas because they are congested.’ Then you will get a better distribution of crowds around those spaces.”

Safe failure mode

Venue designers have to anticipate the worst possible thing that could go wrong and plan for it. Technology needs to be designed around a ‘safe failure mode’, recognising systems don’t always work – and to build in mechanisms so that when they fail, they do so safely. If, for example, a camera which is monitoring wait time breaks, it shouldn’t then broadcast a wait time of zero minutes, but instead go to infinity until the issue is resolved. The biggest threat to fan safety is almost always the fans themselves.

“People can do the stupidest things,” continues Still. “It’s worth imprinting that into people’s minds when they think about crowds. So, how do we consider the implications of that and design safety within those concepts?”

Sports is built on the aspiration of achieving what to some seems impossible. And this human drive – often tweaked by alcohol – creates situations thatget people into trouble. Still cites examples of people trying to climb a 100ft drainpipe to get over the walls at Wembley Stadium – without thinking about how they would then get down the 100ft drop on the other side. Or another, where fans were attempting to get into a venue by knocking faulty hinges off a steel door – which happened to weigh four tons.

Stadiums that are decades old won’t have been designed with this rate of traffic flow in mind. Mass notifications may have a powerful impact on managing crowds, or directing people to better access of services, but these have to be considered in their emotional context. Notifying fans that there’s no wait at the bar almost guarantees a stampede.

“Information systems associated with transit are good and effective,” maintains Still, “providing you understand the consequences of your words. Rather than saying: ‘There are five spaces left in this area’, when you have 1000 people that want to get in, it’s better to say: ‘Avoid the following areas because they are congested.’ Then you will get a better distribution of crowds around those spaces.”

Safe failure mode

Venue designers have to anticipate the worst possible thing that could go wrong and plan for it. Technology needs to be designed around a ‘safe failure mode’, recognising systems don’t always work – and to build in mechanisms so that when they fail, they do so safely. If, for example, a camera which is monitoring wait time breaks, it shouldn’t then broadcast a wait time of zero minutes, but instead go to infinity until the issue is resolved. The biggest threat to fan safety is almost always the fans themselves.

“People can do the stupidest things,” continues Still. “It’s worth imprinting that into people’s minds when they think about crowds. So, how do we consider the implications of that and design safety within those concepts?”

Sports is built on the aspiration of achieving what to some seems impossible. And this human drive – often tweaked by alcohol – creates situations thatget people into trouble. Still cites examples of people trying to climb a 100ft drainpipe to get over the walls at Wembley Stadium – without thinking about how they would then get down the 100ft drop on the other side. Or another, where fans were attempting to get into a venue by knocking faulty hinges off a steel door – which happened to weigh four tons.

“When you examine that from a human perspective, it’s all down to perception of risk and reward. They didn’t perceive the danger of a four-ton steel door falling on them, but they did perceive the reward of getting into a cup final event. The human mind weighs risk, but often incorrectly. We look at it and think it’s really stupid, but it’s all down to how a person’s brain can discern risk and reward.

“You have to consider: ‘What is the stupidest thing that can be done?’ Then assume they are all going to do that,” concludes Still.

This article first featured in the Sept/Oct issue of FEED:Xtreme.

“When you examine that from a human perspective, it’s all down to perception of risk and reward. They didn’t perceive the danger of a four-ton steel door falling on them, but they did perceive the reward of getting into a cup final event. The human mind weighs risk, but often incorrectly. We look at it and think it’s really stupid, but it’s all down to how a person’s brain can discern risk and reward.

“You have to consider: ‘What is the stupidest thing that can be done?’ Then assume they are all going to do that,” concludes Still.

This article first featured in the Sept/Oct issue of FEED:Xtreme.